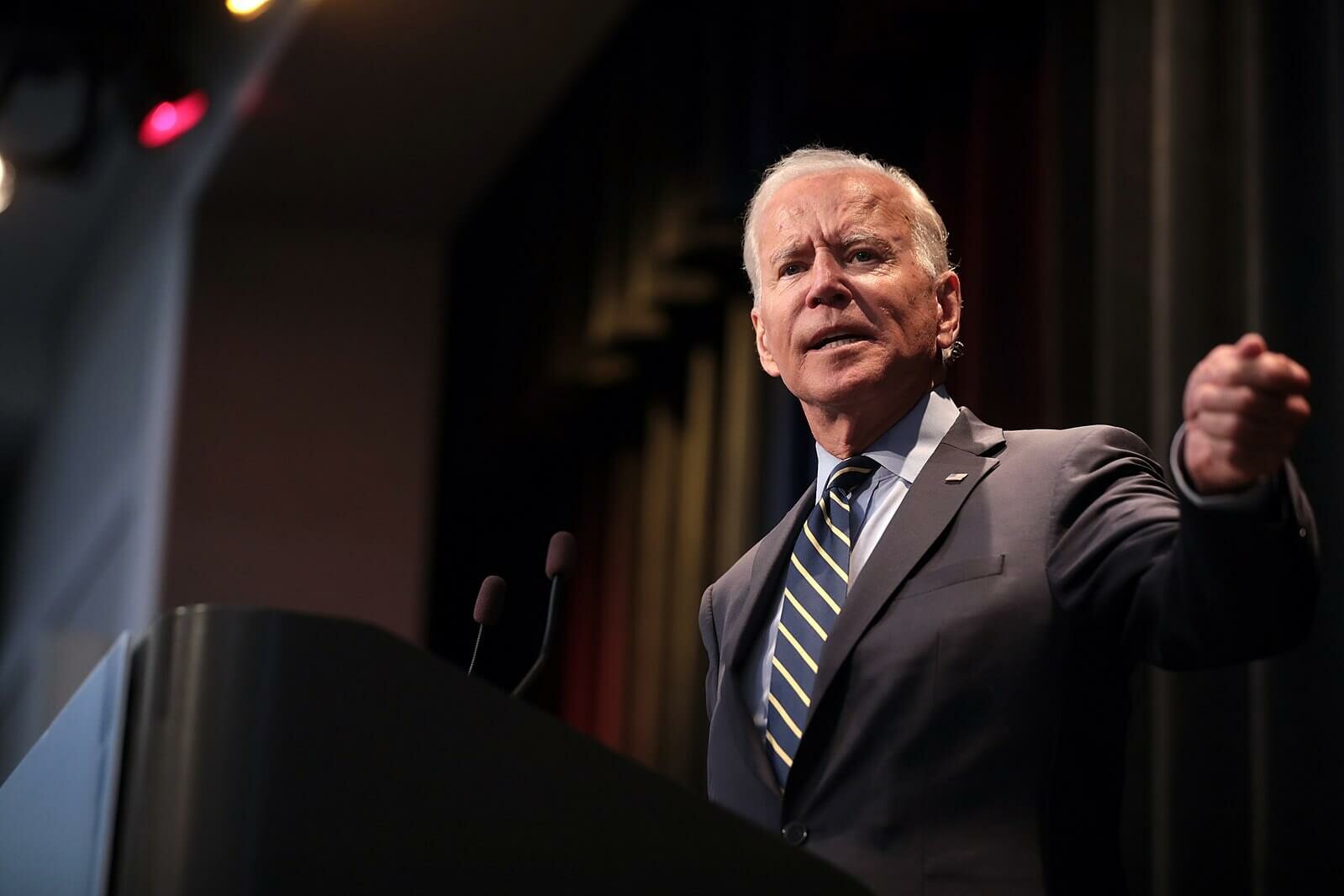

The New Atlantic Charter, signed by President Joe Biden and Prime Minister Boris Johnson on 10 June 2021 on the eve of the G7 Summit in Cornwall, seeks to revive the spirit of Roosevelt and Churchill’s 1941 Atlantic Charter by pledging bilateral cooperation on a series of commitments and aspirations. Speaking to the press a day later, Johnson depicted the US-UK alliance as the ‘indestructible relationship’.

From a nuclear arms control watcher’s perspective, a notable innovation of the Charter is paragraph seven, where the two countries ‘pledge to promote the framework of responsible State behaviour in cyberspace, arms control, disarmament, and proliferation prevention measures to reduce the risks of international conflict’.

The language of ‘responsible State behaviour’ has provided an important normative framework for the development of norms in cyberspace and more recently the UK government has pressed this language into service when it sponsored UN General Assembly Resolution 75/36, ‘Reducing space threats through norms, rules and principles of responsible behaviours’. Support for both ‘international law and voluntary norms of responsible state behaviour in cyberspace’ and ‘international efforts to promote responsible behaviour in space’ was echoed four days after the signing of The New Atlantic Charter in NATO’s 14 June Brussels Summit communiqué.

This is the first time that the specific language of ‘responsible state behaviour’ has been used publicly in an official capacity in relation to nuclear weapons. This ‘responsibility turn’ in security provides an important direction of travel for future bilateral and multilateral discussions to reduce distrust and the growing risk of nuclear conflict, and could form the normative basis of an integrated framework of responsible behaviour to stabilise and enhance international security.

A Responsibilities-based Approach to Nuclear Weapons?

Exploring the possibilities for a new dialogue on responsibility in relation to nuclear weapons has, since 2016, guided the Programme on Nuclear Responsibilities, a joint project between BASIC and the Institute for Conflict, Cooperation and Security (ICCS) at the University of Birmingham. Between 2018-2019, we organised a series of ‘proof of concept’ track 1.5 meetings with a diverse set of stakeholders in the capitals of five states with traditionally different perspectives on the legitimacy of nuclear weapons: Brazil, Japan, Malaysia, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom. We then brought officials from those five states together in London for a dialogue to reflect on the findings from the meetings in January 2020.

The results were extremely positive, with parties indicating that they saw great potential for a shared dialogue on responsibilities in relation to nuclear weapons to gradually shift the nature of the contemporary global conversation away from one characterised by rights, blame, and suspicion towards one framed by responsibility, empathic cooperation, and even trust – all of which are currently lacking in the habits and practices of international nuclear diplomacy.

We have formalised this support and earlier explorations into the Nuclear Responsibilities Approach: an approach to thinking, talking and writing about nuclear weapons that aims to put a meaningful exploration of stakeholders’ responsibilities at the centre of our nuclear cultures, mindsets, dialogues, and publications. The Approach is set out in theoretical terms in Nuclear Responsibilities: A New Approach for Thinking and Talking about Nuclear Weapons (2020), and is further detailed in more practical terms in The Nuclear Responsibilities Toolkit, which will be published in August.

This work has had an influence on the UK Government, which has put its backing behind the project. Last year, at the November launch event of Nuclear Responsibilities, Head of the Counter-Proliferation and Arms Control Centre, Sarah Price, stated that the United Kingdom would no longer refer to itself as a ‘Responsible Nuclear Weapon State’ due to the controversial nature of this language among many Non-Nuclear Weapon States (NNWS). Instead, the UK committed itself to deepen its understanding of its own ‘responsibilities’ and invited others – governmental and non-governmental – to do the same.

This commitment was backed up in the March 2021 Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy, where the United Kingdom was instead framed as a state that ‘takes its responsibilities as a nuclear weapon state seriously and will continue to encourage other states to do likewise.’ Recent drafts of the UK’s National Report to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) Review Conference reiterate this theme. Consequently, in October 2021, BASIC and the ICCS convened a day-long meeting at the British Academy with officials and non-governmental experts to further explore just who the United Kingdom has responsibilities to, what their responsibilities are, and how they are discharged in state policies and practices.

It seems likely that the UK’s exploration of a responsibilities-based approach to space, cyber, and now perhaps nuclear, diplomacy contributed to the inclusion of the ‘responsible state behaviour’ language in the New Atlantic Charter. The framing also deftly sidesteps the contentious question of whether there can be such a thing as responsible behaviour with nuclear weapons (as former UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon would say, ‘there are no right hands that can handle these wrong weapons’), by concerning itself only with behaviour in relation to arms control, disarmament, and proliferation.

A Responsibility to Reassure

If the goal of nuclear risk reduction is to be achieved, then any framework of responsible state behaviour will have to encompass adversaries as well as allies. Six days after Biden and Johnson had signed the New Atlantic Charter, the US president met with his Russian counterpart Vladimir Putin in Geneva. Going into the summit, Biden emphasised the ‘incredible responsibilities’ both countries shared for managing global security challenges, including crucially ‘ensuring strategic stability’.

Amidst increasing tensions in the wider bilateral relationship, and thirty-six years after Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev had de-escalated US-Soviet tensions with their statement at the 1985 Geneva summit that ‘a nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought’, Biden and Putin reaffirmed this commitment in a ‘Presidential Joint Statement on Strategic Stability’ that committed both sides to a new ‘integrated bilateral Strategic Stability Dialogue’ that could ‘lay the groundwork for future arms control and risk reduction measures’.

At the press conference following the summit, Biden said he ‘told President Putin that we need to have some basic rules of the road that we can all abide by’. One important principle endorsed by Reagan and Gorbachev in 1985 was that neither side would ‘seek to achieve military superiority’. This principle of responsible state behaviour could be endorsed again by today’s leaders, thereby limiting the risk that either side will seek to pursue strategic superiority in any of the domains (e.g. nuclear, space, cyber etc.) of security competition.

Biden further emphasised that what was needed was a new ‘mechanism that can lead to control of new and dangerous and sophisticated weapons’. The proposed Strategic Stability Dialogue could be such a mechanism, and its success will depend upon both sides agreeing what counts as ‘responsible state behaviour’ in the context of new technologies that have such potential to disrupt strategic stability. US-Russia strategic stability is often framed as a condition, but it is better conceived as a relationship that requires continual management and attention, and this is where such a dialogue becomes so important.

The hazards that must be avoided are two-fold: first, the Biden Administration, whatever its disagreements with Russia in other areas of foreign policy, should avoid the temptation to impose its (Western-centric) conception of the rules on Russia; such a course will only serve to fuel the distrust that currently exists between the two sides. Second, the rules of responsible state behaviour must be sufficiently determinate so that they are not open to misunderstandings and misperceptions, as happened in the détente period between the United States and the Soviet Union in relation to divergent interpretations of what was permitted under 1972 Basic Principles Agreement.

A Multilateral Nuclear Dialogue

However, the task of achieving nuclear risk reduction through constraining destabilising technologies cannot be restricted to the big two. It must also embrace China, the wider P5, and indeed the other nuclear-armed states. Extending the ambit of responsible state behaviour to encompass these states could be achieved if the Biden Administration takes the following steps.

First, working with its allies in the P5, the US should support China’s earlier recommendation – recently reinforced by a coalition of NGOs and luminaries – that the P5 affirm its collective and unwavering commitment to the Reagan-Gorbachev principle that ‘a nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought’. China, Russia and the United States have already committed themselves to this principle, leaving France and the United Kingdom in the minority.

Second, and more ambitiously, the United States – perhaps working initially through the Creating an Environment for Nuclear Disarmament (CEND) mechanism which brings together both NPT and non-NPT state parties – should encourage the four nuclear-armed states outside the Treaty (N4) as well as all non-nuclear weapon states to sign on to the Reagan-Gorbachev (and now Biden-Putin) statement. The inclusion of NNWS would symbolise global unity behind this principle, as well as provide diplomatic cover for those states with undeclared nuclear arsenals.

The obvious mechanism for such a collective declaration would be a UN General Assembly Resolution. And although the views of all states and many non-governmental stakeholders should be recognised as equal in this critical debate, the P5 have a special responsibility to lead it. It is sixty years this December since the UN General Assembly approved Resolution 1665 on “Prevention of the wider dissemination of Nuclear Weapons”. The so-called “Irish Resolution” after the pioneering efforts of Frank Aiken, Ireland’s Minister of External Affairs, laid the groundwork for the adoption of the NPT itself. What more fitting and important tribute could there be to the work of their predecessors than for the UN General Assembly to enact a new resolution that establishes a comprehensive normative framework of responsibilities in relation to nuclear weapons.

This article has been written by Sebastian Brixey-Williams, Dr. Rishi Paul and Professor Nicholas J. Wheeler.