This is a guest op-ed from Daniel Allen, a student researcher associated with the Middlebury Institute for International Studies at Monterey focused on nonproliferation and arms control through open-source intelligence collection.

Every day, by default and inaction, the global citizenry supports a system that could end the world in an hour. And until the popular discussion around nuclear weapons is revitalised, we will continue to be held unwitting hostages by them. This revitalisation process must include the reignition of public interest — but how do we do this when honest representations of nuclear weapons and their costs are not present in the stories we regularly read and watch?

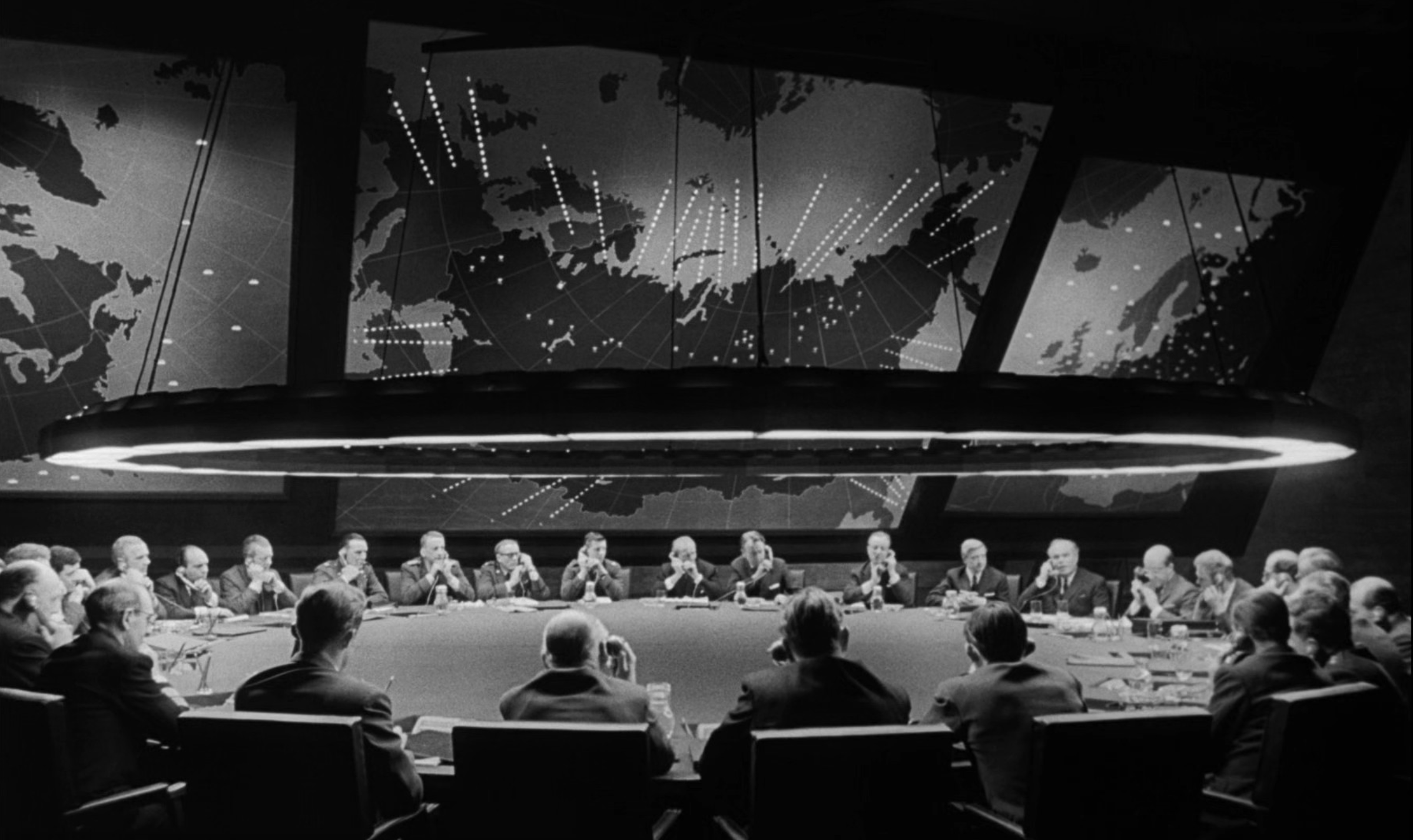

It was not always this way. In the 1950s and 1960s, nuclear weapons enjoyed a unique presence in the minds of the public conscience. Films such as Doctor Strangelove (1964) and books like On the Beach (1957) became household names; media helped bridge the gap between academics and the public, showing the horrifying outcomes of nuclear exchanges and ultimately paving the way for the golden age of nonproliferation. Today, however, the popular discussion of nuclear weapons and nonproliferation has largely been sidelined by both policymakers and the public in favour of other issues.

Why the widespread apathy?

Because we made the nuclear field so abstract and sterile that the public cares little about engaging with it.

Successful political issue campaigns are rarely grounded on dry theory, but rather on emotive issues that evoke the public to act. After the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the ever-present danger of the Cold War, the public conscience worked to ensure such horror never happened again. We were not motivated by abstract calculations of power parity and deterrence theory, but by the existential threat collectively understood through its prominence in politics and media. As our nuclear discourse has narrowed, policymakers are able to listen more selectively to the voices that speak on this issue and tailor policies to interest groups incentivised to maintain and expand the nuclear weapon regimes.

Yet daily life in the nuclear policy community, both amongst defence scholars and policymakers, does not include the profoundly moral questions that echoed around kitchen tables across the world. We sanitised the subject, reducing horrific human costs into neat calculations that serve as justifications for the continued presence, and expansion, of our nuclear stockpile. As Carol Cohn called it: clean bombs and clean language. Countervalue targeting is much more palatable in daily life than targeting civilians and population centres with nuclear weapons. These weapons of mass destruction are couched into playful terms such as Slick’ems, Laughing Buddha, and Little Boy, further removing us from the true essence of our work. This makes it easy to be complacent; to surrender to the assertion that these sterile systems are beyond reproach and are a fact of life to be accepted, rather than resisted.

But now is not the time for complacency. We currently stand in an unprecedented era of international tension between nuclear-armed states. Russia continues its invasion of Ukraine with nuclear “red line” rhetoric, while the United States and China modernize their nuclear arsenals. Meanwhile, North Korea continues to develop and test its nuclear-capable ballistic missile program with no signs of slowing.

Simultaneously, the nonproliferation regime is experiencing enormous setbacks as major powers suspend and pull out of arms control agreements (the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty, Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty, Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty, or the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, just to name a few). This has given way to increased testing, decreased oversight, and growing distrust. Non-use norms established as stabilising are backsliding as leaders ramp up their nuclear rhetoric and begin to employ nuclear weapons as coercive tools.

We are now faced with a growing number of emerging technologies such as AI, hypersonic weapons, lethal autonomous weapon systems, and cyber warfare, that threaten global stability with only limited heuristics available to the international community. There is a dire need for revitalised public interest in the nonproliferation regime and a re-engagement in nuclear policy to push policy makers out of complacency.

Art has the power to convey the essence of ideas, both emotional and intellectual, and this is why it is such a salient medium for discussing nuclear weapons. It can distil complex ideas into a form that resonates with a wider audience.

Doctor Strangelove expertly distils the dangers of deterrent-based logic and the fragility of America’s command and control structure. When I watched it for the first time, none of the technical terms meant anything to me, and yet the essence of the ideas came through.

Film, music, and literature can highlight the extreme academic rationalisation present in the public nuclear policy debate, parodying an otherwise clinical topic and laying bare the dangers that lie dormant beneath theoretical frameworks. In essence, art provides a ladder set against the ivory tower, making nuclear policy accessible to the public and fostering a space for meaningful, inclusive dialogue, creating an opportunity for a parallel discourse on nuclear issues from civilian interest groups to complement those of IR scholars and policymakers.

The exclusion of the wider public from nuclear policy does not need to be the status quo. We can draw on lessons from the past to show the importance of popular media in bringing about awareness and education. The 2023 film Oppenheimer proved how art can spark public debate. With an exclusive focus on the development and consequences of nuclear weapons, it served as an entrance into an otherwise inaccessible field for a vast amount of people. But it need not stop there. With the advent of new technologies our learning environments have broadened and we have changed what it means to interact with media. Blending large language models and mixed, or virtual, reality systems, we are now able to reproduce environments that simulate decision-making in nuclear contexts, showing the fragility of our current deterrence theory, the vulnerability of high-tech systems, and ultimately the consequences of a nuclear exchange. We are not talking abstract theory here: strides in this field have already been made by Moritz Kutt and Sharon Weiner who use virtual reality to create nuclear scenarios open to the public that simulate the American decision-making process.

Nuclear weapons affect all of us, regardless of our nationality or identity, and it is a fundamental democratic duty to be engaged in this debate not just for ourselves, but for all humanity. There are no right hands for these wrong weapons, but a shared responsibility is better than no responsibility at all. It is time to give back the nuclear question to those whom it affects: all of us.