The infamous maiden voyage of the Titanic in April 1915 forms a totemic story of misplaced arrogance and disastrous overconfidence familiar to everyone. But the Dreadnought battleships (the first launched nine years earlier) have a similar and just as powerful a narrative for the Navy. In his chapter ‘Dreadnought Science: The Cultural Construction of Efficiency and Effectiveness’, Crosby Smith outlined the roll call of Dreadnought battleships lost in the world wars. ‘In almost every case, around a thousand men died, victims – it has been argued – less of direct enemy action and more of the ‘failures’ of the design of these leviathan symbols of sea power.’ He quotes Robert L. O’Connell’s words, ‘[the Dreadnoughts] sheer attractiveness, the degree to which it fulfilled people’s conceptions of what a weapon should be, caused it to generate tremendous respect, loyalty, and unwarranted longevity’.

The fact that the Ministry of Defence last week chose to name the first of the next class of nuclear ballistic missile submarines HMS Dreadnought has such a delicious irony to it. It is difficult to not to suspect that some within the system are trying to send us a message.

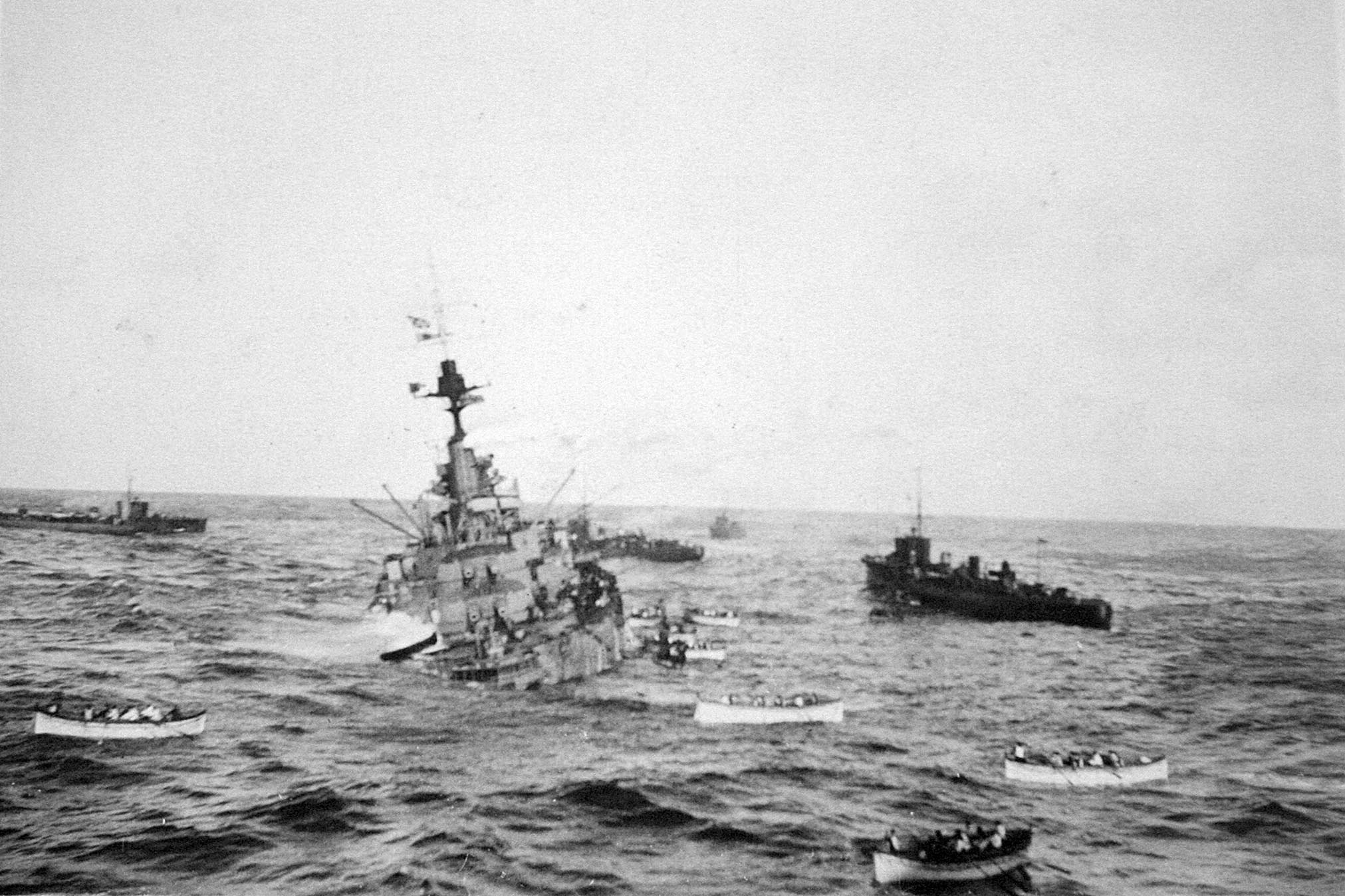

The Dreadnought battleship programme at the beginning of the 20th century was a massive drain on the defence budget, just as the forthcoming submarines will be. It was considered to be in a completely different class to previous battleships, with such extraordinary capabilities that it could determine the outcome of the war. HMS Dreadnought was an obvious propaganda symbol of national jingoism and British imperial status, launched with great fanfare in 1906. In subsequent years, the naval race gripped Britain, Germany and Japan with equal measure. Dreadnoughts became the very essence of the arms racing that students of the period identify as one of the main causes of the Great War. And yet they had little to no impact on its campaigns or its outcome. It was a technology that was the logical extension of nineteenth century naval power, but was already vulnerable to torpedoes and submarines.

Of course, the naming of the new submarine also recalls the Royal Navy’s first nuclear-powered submarine, HMS Dreadnought (1960), the first-born offspring of a momentous new era in US-UK nuclear cooperation after the messy Suez Crisis. As the Anglo-American relationship is tested by Brexit and movements by Russia, the Successor submarine harks back to those heady college days, in which the UK was finding its nuclear feet with the help of its older Atlantic brother. That, as Hennessy and Jinks point out, a ‘”major controversy” was raging behind the scenes between proponents of the nuclear submarine and those who supported the development of a nuclear-propelled surface ship’ (2015, p.170) is now largely forgotten. Like today, cost was a primary factor, though it was overridden by a government that refused to row backwards.

Commentators often refer to the Trident system as a political weapon, and the naming of the platform after such symbols shows the kind of politics it is intended to convey: an imagined imperial majesty that is both factually inaccurate and culturally inappropriate, and a nostalgic loyalty to the US with echoes of both complacency and anxiety.