On 23 November, the day the Strategic Defence and Security Report (SDSR) was released, former Defence Secretary Lord Browne warned of the possibility that the UK’s nuclear deterrent, Trident, will likely be rendered ‘obsolete’ by cyber-attack in future. The SDSR announced an increase in the budget for the renewal of the SSBNs for the Trident system to £31bn (with an additional £10bn contingency fund), and Chancellor George Osborne announced an additional £1.9bn for cyber investment. This raises a number of questions over the effectiveness of any strategy to address cyber vulnerabilities, and what this means for assurance in the reliability of strategic nuclear weapon systems.

Threats arise from traditional state actors, as well as hacktivists (combining elements of hacking, and activism to promote political goals), terrorists and other non-state actors. The latter is often the threat that attracts most attention, but the former, from state actors, is probably more capable. All states suffer a constant and increasing barrage of cyber attacks. Last year North Korea suffered the theft of privy information to its nuclear facilities including blueprints of at least two nuclear reactors. The more widely reported Stuxnet attack on Iran’s Natanz nuclear enrichment facility and Bushehr nuclear power plant in Iran resulted in the disintegration of 1000 centrifuges, and is believed to have set back the programme many months, perhaps years. This attack was later attributed to a joint effort between Israel and the US, although denied.

More generally, the potential impacts from cyber attacks go way beyond denial of service, loss of critical information or the destruction of targeted activities. Ultimately, when targeting critical national infrastructure, they can lead to a widespread loss of power, the release of uncontrolled ionizing radiation, or a variety of other critical and deadly impacts on physical and psychological public health, the ecosystem as a whole and of course, the economy. One only needs to assess the widespread impacts from the Fukushima incident in Japan to understand the potential.

There are several features of cyber attacks which exacerbate the problem. They are generally invisible (beyond obvious outcomes) and attribution is extremely problematic. This makes deterrence or defence generally very challenging. They are numerous and their frequency is increasing, which also presents major challenges, not only for overwhelming efforts to prevent or respond, but also presenting complexities when attacks are either coordinated or unintentionally interact to overwhelm defences or create wicked impacts.

Suspicion or a lack of restraint in exercising cyber capabilities could have political or diplomatic spillovers, blighting relationships between states once the aggressor states are revealed. Beyond this, non-state actors like ISISalso pose cyber security threats of a different nature. ISIS widely uses social media platforms for recruitment, and they recruit individuals with unprecedented levels of technical IT capabilities and ability to penetrate Western civil and military technology systems. Nuclear weapon systems are not immune to this threat.

But perhaps the bigger cyber threat to the integrity of strategic systems comes from other states. A US Defense Science Board report, describes the likelihood that the reliability of strategic nuclear systems have already been compromised by foreign powers. As the trends in this area can only develop further (offensive cyber will always outstrip defence capabilities), the credibility of nuclear deterrence can only degrade over time. This is about the reliability of command and control and the firing chain, not so much the danger of unauthorised launch as the high probability of malicious code preventing launch at critical moments.

George Osborne’s £1.9bn plan is targeted on four main elements:

- International diplomacy to establish norms governing cyber-warfare and international law hold cyber criminals accountable;

- Boosting the National Cyber Crime Unit;

- Developing a skilled cyber work force; and

- Cooperating with cyber start-ups such as GlassWall.

Osborne also spoke of his intention to undermining the idea of impunity in hyperspace by announcing a cooperation between MoD and GCHQ to establish deterrence with a national offensive cyber capability. Where this leaves assurance over the future reliability of the firing chain for Trident remains to be seen.

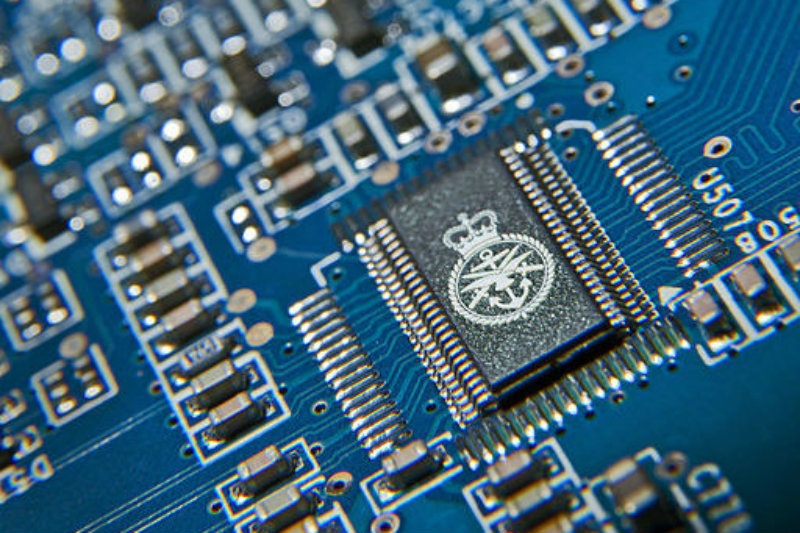

Photo: Chris Roberts/MOD [OGL (http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/1/)], via Wikimedia Commons