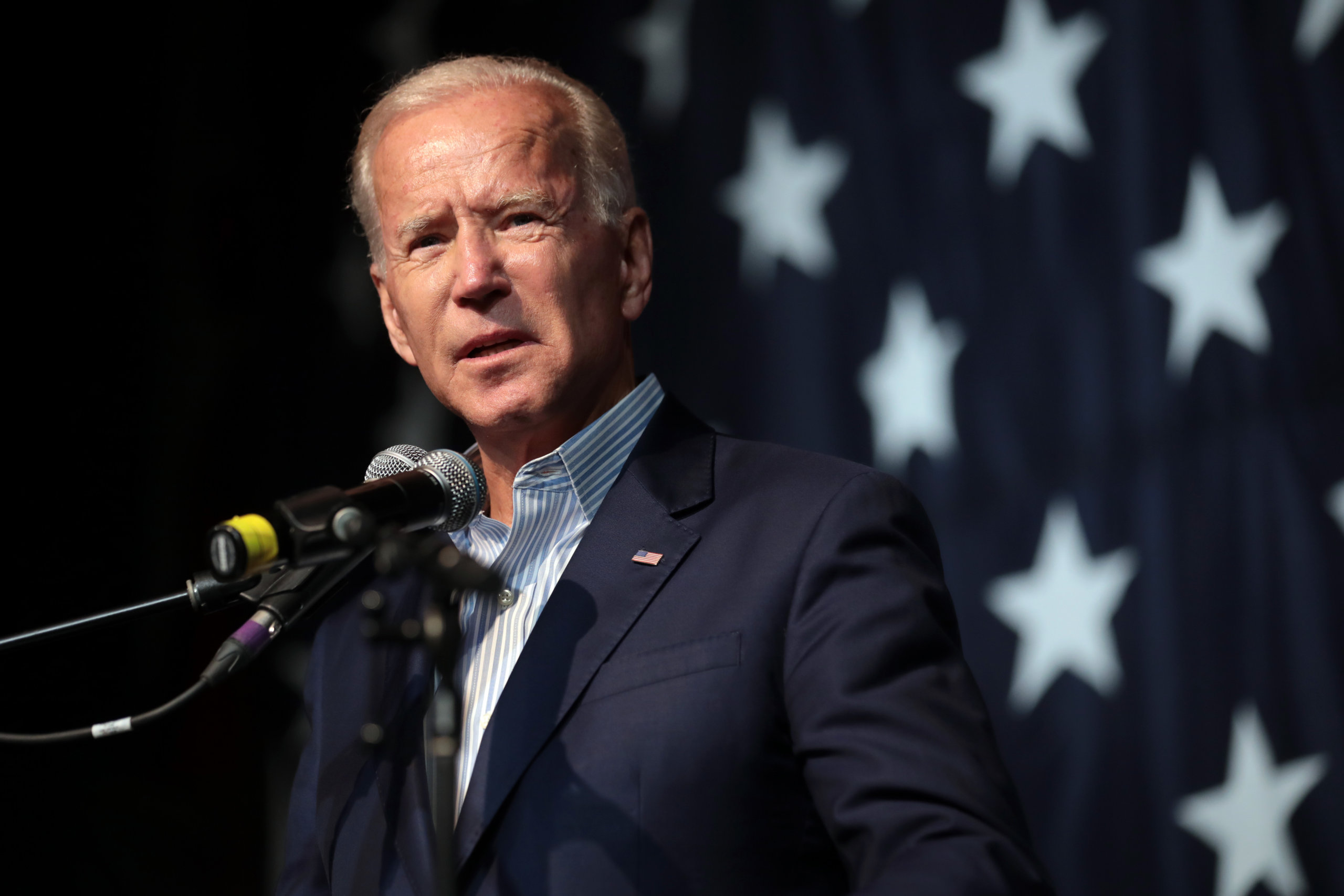

The world is waiting with bated breath for the outcome of the United States presidential election on 3 November, which will determine – among other things – the future direction of US foreign and defence policy. Former Vice-President, Joe Biden, is presented as a safer pair of hands than President Trump, yet how far could a Biden Administration be expected to deliver a truly different nuclear weapons policy? The answer to this will significantly impact European security – not least the United Kingdom, which relies on the United States to modernise the nuclear warhead for its Trident nuclear submarines.

US Commitment to Multilateralism

The first central difference between a Biden or Trump nuclear weapons policy is their starkly opposed perspectives on multilateralism and alliances. Over the last four years, the Trump Administration has sought to withdraw the United States from its lead international role and withdrawn from key nuclear agreements, including the INF Treaty, Treaty on Open Skies, and the Iran Nuclear Deal. President Trump has even reportedly discussed withdrawing from NATO, which would leave the UK and France as the Alliance’s sole nuclear powers at a time NATO is facing ‘unprecedented challenges’. In contrast, Biden explicitly advocates for the United States to return to ‘the head of the table’, seeing allies not as a burden but rather as central underpinnings of US power.

Whoever wins the election could also have consequences for US extended deterrence: the guarantees that the United States makes to defend its allies and partners from external threats. A Trump Administration could continue to withdraw forward-based troops from mainland Europe (as happened recently in Germany), potentially removing conflict ‘tripwires’ that could act as deterrents to foreign intervention, damaging US commitment to European security. With allies already doubting the Trump Administration’s commitment to alliances, efforts to retreat from NATO would further throw into doubt the United States’ commitment to the ‘nuclear umbrella’.

How far could a Biden Administration reverse these patterns? It may not be as easy as simply re-signing the treaties exited during the last four years. With trust eroded in the United States’ good faith and willingness to remain party to commitments under international treaties, a Biden Administration may have a hard time convincing others to sign on to new treaties, or restore old ones – if there is even a treaty to go back to. An important test-case will be whether Biden can salvage the Iran Nuclear Deal, or replace it with something else which limits Iran’s current nuclear programme.

But it will take more than trying to press the reset button on the last four years. Firstly, it needs to be better understood which recent changes to alliance relationships have been the result of the Trump Administration’s actions, and which are reflective of more structural, longer-term divergence between the US and its allies’ interests. Secondly, it is unclear whether allies would regard a Biden Administration as a return to the past, or a brief respite from a new direction in U.S. foreign policy, accelerated over the past four years. Thirdly, even a restoration of alliances under a Biden presidency may not be enough to make them effective against rapidly emerging trends and threats, such as disinformation, hypersonics, and Artificial Intelligence (AI). Mitigating these threats will also require alliances to be coordinated and transparent. Simply recommitting to alliances is likely not enough to re-secure the United States’ position at ‘the head of the table’.

The Future of Arms Control

Arms control has suffered substantially over the past half-decade. Citing concerns with Russian non-compliance, the United States has withdrawn from all-but-one of the Cold War bilateral arms control agreements. New START is the only remaining treaty, but it’s February 2021 renewal deadline looks uncertain to be met, despite recent talks. A second Trump Administration may seek to reiterate its call for any future arms control agreements to be trilateral – involving the United States, Russia, and China – but there remain few incentives for China to take part. In contrast, Biden has already stated his desire to ‘immediately’ renew New START; but this alone is unlikely to reverse the longer-term consequences of actions by the Trump Administration, and will not resolve longstanding questions over arms control.

Beyond trilateral or US-Russian arms control, there has been no tangible progress with North Korea. Conducting one meeting without senior North Korean representatives and one ending with love letters, the Trump Administration has left Biden with a low starting base from which to work from. If President Trump secures another term, with arms control ‘almost dead’, the future looks bleak for nuclear treaties. Without treaties limiting the number or type of nuclear weapons possessed by signatories, and without a direct line of communication between adversaries, uncertainty increases, as does the risk of miscalculation fuelling a crisis. This is a severe concern for both US and global security.

Nuclear Modernisation

Differences between a Biden or Trump Administration on US nuclear modernisation are more limited than they might first appear. Expanding President Obama’s estimated $1.2 trillion nuclear modernisation programme ($1.7 trillion once inflation is accounted for, which works out at roughly $6.5 million an hour), President Trump has committed to upgrading ‘nearly every element of the U.S. nuclear arsenal…over the next twenty years’. In contrast, it is hoped Biden could cut modernisation costs and redirect funds. In theory, cuts should be possible: ‘most of these [modernisation] efforts are in the early stages, and a few others have yet to begin’. Former officials have also spoken out against modernisation, including former Secretary of Defence William Perry calling for scrapping the US ICBM programme, in his book with Tom Collina, ‘The Button’. However, there is largely bipartisan consensus on the overall direction of modernisation, with only differences around the margins.

Should Biden choose to limit nuclear modernisation, two further factors will undermine his ability to make substantial changes. Firstly, powerful defence contractors wield influence in Congress. For the modernisation of ICBMs alone, Northrop Grumman won a sole-sourced contract worth over $13bn. Such an environment creates ‘little or no pressure in Congress to scale [modernisation] back’ – a lesson quickly learned by President Obama. Secondly, the narrative that big defence spending contributes to US jobs sells well with the domestic public. Countering this narrative would likely be unpopular domestically, particularly with an economic crisis looming. However, with hundreds of thousands of Americans losing their lives from COVID-19, the pandemic could require a reconsideration of US funding priorities. And if a Biden Administration did limit nuclear modernisation and the new W93 development warhead was scrapped, the UK could find it significantly harder to carry out the replacement of its own warhead.

US Declaratory Policy

The policy area that could see the most dramatic change is US declaratory policy: the public statement of when, how, and at what scale the United States would be willing to launch a nuclear attack. While the Trump Administration in the 2018 Nuclear Posture Review widened the circumstances in which it would consider nuclear use to include ‘significant non-nuclear strategic attacks’, Biden has spoken of the sole purpose of US nuclear weapons as being to deter a nuclear attack.

Election promises are one thing. Whether Biden would pursue a change in US declaratory policy upon winning office is another question. For someone who champions alliances, altering declaratory policy Biden could yet undermine the solidarity of US alliances and nuclear assurances to allies, particularly among the Baltic States, Japan, and South Korea.

Biden also considered questions of declaratory policy last time he was in office, so the reality of changing US declaratory policy whilst simultaneously attempting to strengthen alliances is harder than the fiction. Moreover, given the significance of Russia and China to the United States’ sense of insecurity, any changes in US declaratory policy would likely be at-least in part dependent upon Russian and Chinese policy.

Conclusion

Despite the polarised temperaments of candidates, whether Americans vote Democrat or Republican on 3 November, there will likely be much continuity in nuclear weapons policy, despite declarations in campaigning. Although a Biden Administration would herald a more collaborative policy approach, including reprioritising alliance relationships, constraints such as powerful defence contractors funding nuclear modernisation and lasting implications of the Trump Administration’s actions towards alliances, adversaries, and international treaties, will place limits on how much can be achieved in practice. Biden is sure to feel the lessons of ‘saying is harder than doing’ even more acutely than his former boss, Barack Obama.

Finally, it is yet unclear how far allies and adversaries would consider a Biden Administration to be an enduring return to the status quo, or a brief four-year holiday from a new American approach facilitated by President Trump. All this being said, Biden still offers a more restrained and collaborative approach than a Trump Administration, and this would be a good thing for global security – if not quite the fairy tale alternative often imagined.

Disclaimer: This article was written by a former member of the BASIC staff. Views expressed belong solely to the original author of the article and do not necessarily represent the views and opinions of BASIC.

Image: Gage Skidmore, Flickr, CC 2.0.